27. Street Extension

27.1. General principles

Street extension occurs at the end of rows of terraced, detached or semi-detached houses where a plot of land is, or can be made, available for redevelopment.

Such sites often exist along secondary streets where a row of terraced houses meets the rear garden of property facing a primary street. These sites are sometimes occupied by existing garages or outbuildings, or in other cases form the end of long gardens with a boundary onto a road.

To qualify as a street extension a site must have a frontage directly onto a public highway.

27.2. Single dwellings

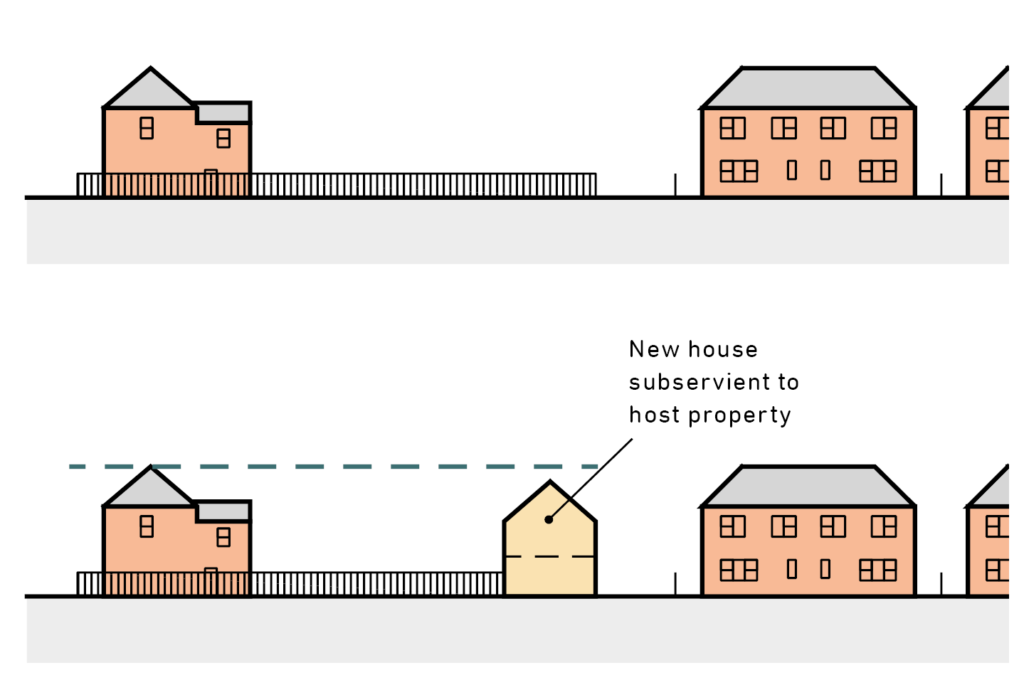

The simple extension of an existing terrace or row of houses can often provide sufficient space for a new family home.

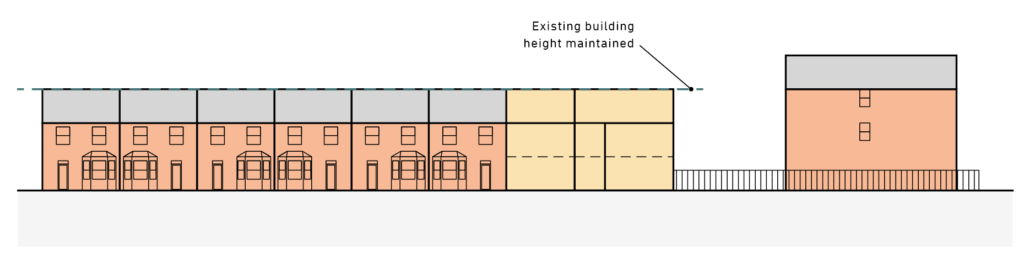

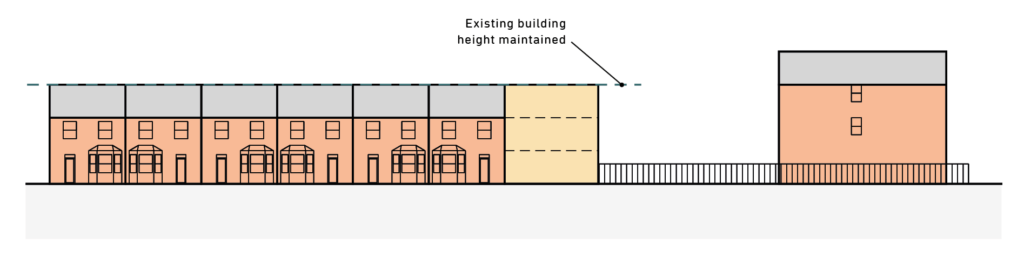

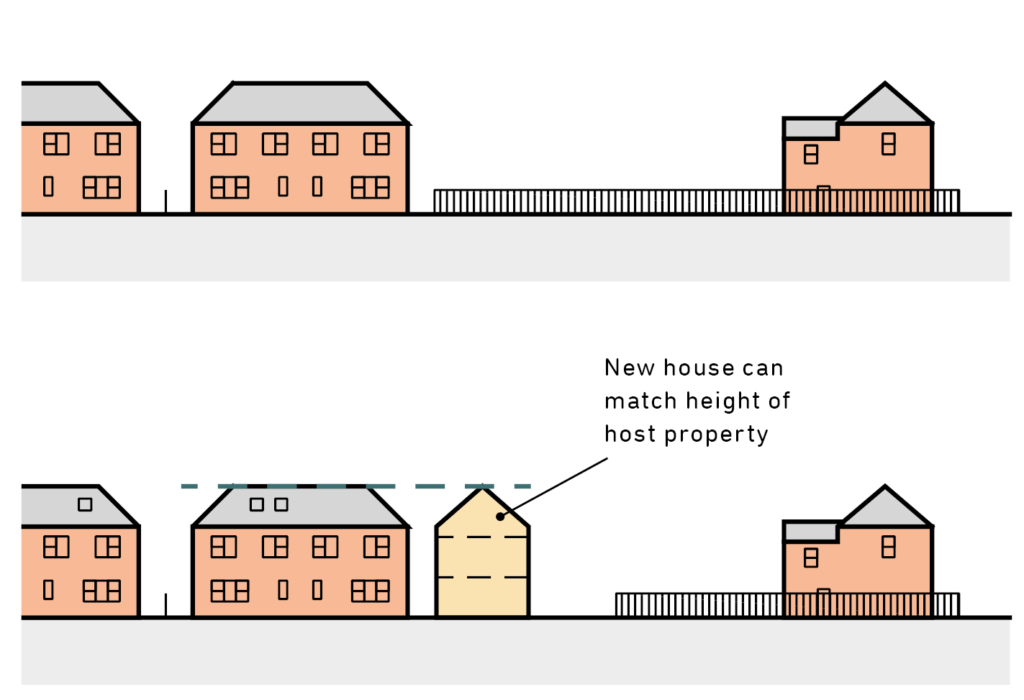

The height of street extension development should generally follow that of the closest neighbour on the street it is extending, taking into account that – in most cases – a pitched roof can be counted as a floor.

Street extension development should generally maintain the existing building line established by the street that it is extending. Bay windows, projecting windows and porches are an exception to this rule, providing that they are subservient to the main building.

Street extensions providing a single dwelling will usually be limited in depth to the width of the plot in which they sit. In this case external amenity space will usually be required to one side of the dwelling, rather than at the rear.

To accommodate the required internal floor area, and to provide all habitable rooms with an aspect, the primary aspect for new dwellings will usually be towards the street, with the potential for further windows in the side or rear.

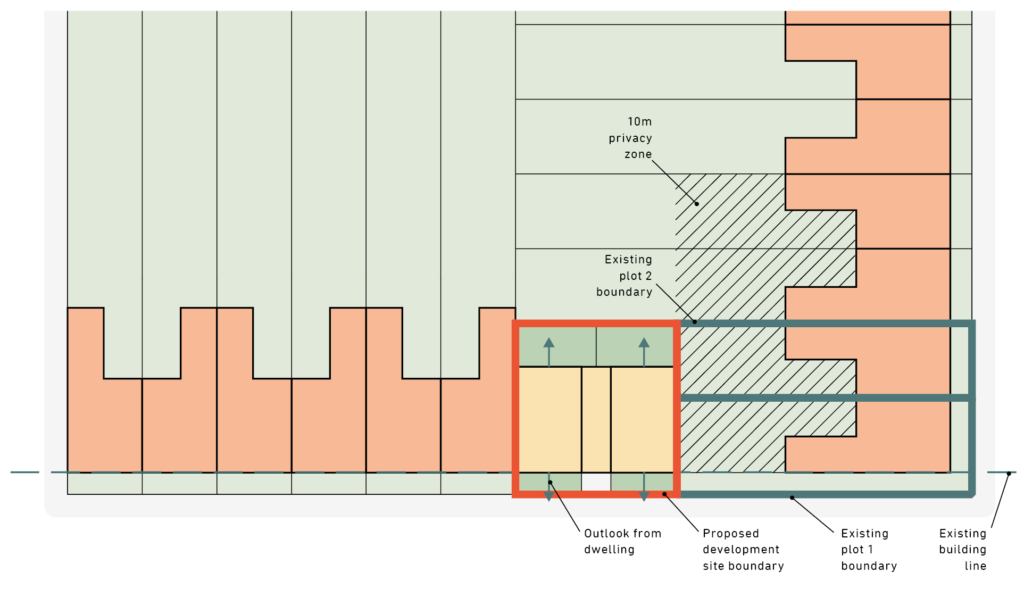

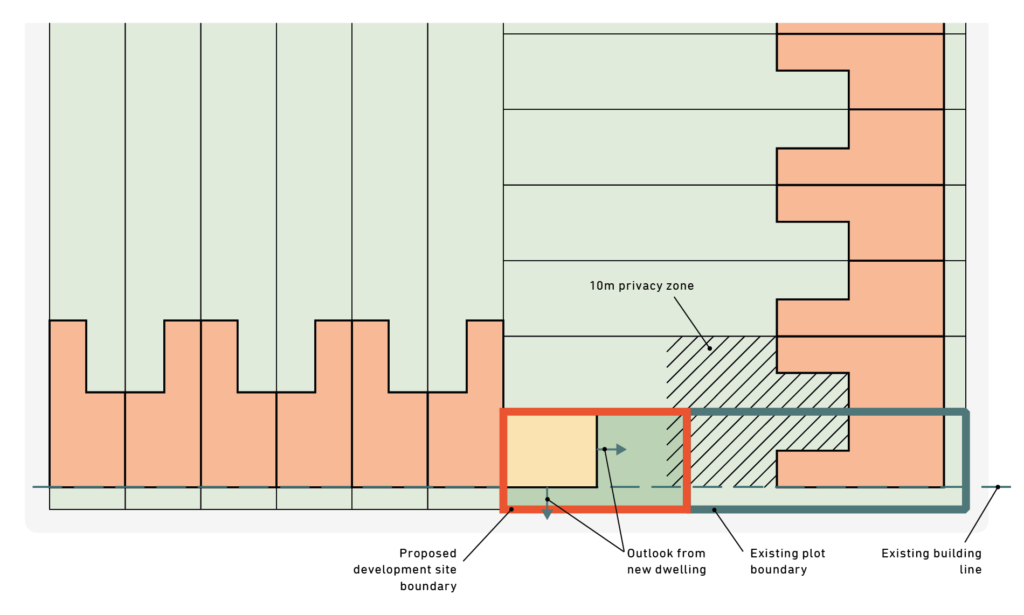

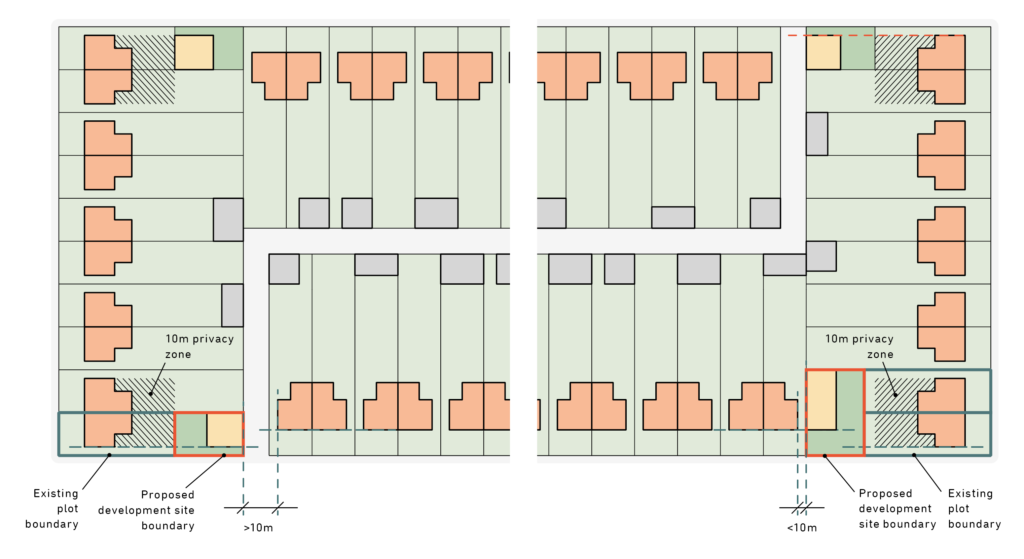

However, direct overlooking of rear gardens should be avoided where possible, and permission for new homes which include windows serving habitable rooms will not generally be allowed where these look directly onto the first 10m of a rear garden.

More flexibility with regards to overlooking of rear gardens can be applied between new and existing properties where these are part of the same development plot.

Distances between the principal windows serving habitable rooms should generally exceed 16m, however flexibility can be applied for new dwellings constructed within the boundary of an existing property, or where adequate steps have been taken in the design of these windows to maintain privacy.

Such development may result in a largely blank wall facing onto an existing neighbouring garden. In this case, even where such elevations lack windows to avoid overlooking, the design and choice of materials used should be carefully considered. Applications will need to demonstrate how the design of side elevations are not overbearing when experienced from the rear gardens of neighbouring properties. Vertical greening of such walls is one mitigating strategy.

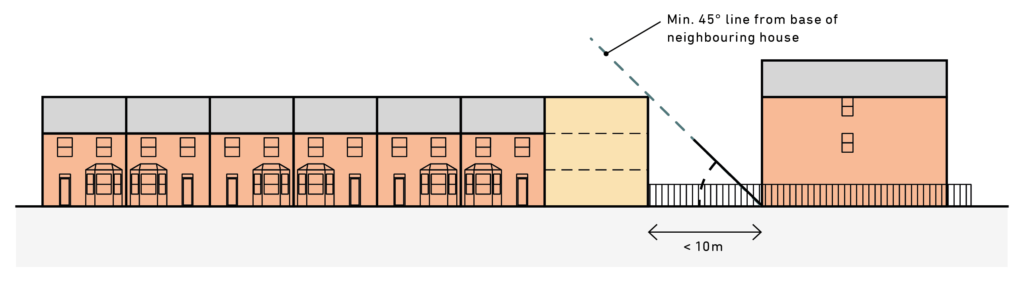

Where the distance between the primary window serving a habitable room and the side elevation of new development is less than 10m, the height of the new wall should not exceed the depth of the garden measured from the rear part of the existing house. The principles described in section 12 should also be taken into account to ensure existing windows receive adequate levels of natural daylight and sunlight.

To ensure that the gardens of the host property continue to enjoy sufficient natural daylight, the principles of the BRE Guidance should be adhered to, and applications will need to demonstrate that new development does not reduce daylight reaching existing gardens to an unacceptable degree.

27.3. Street extension with mews and alleys

Street extensions can also apply in areas where existing properties are more widely spaced apart. Often this condition coincides with the presence of an entrance to existing mews or alleys, or to a backland site.

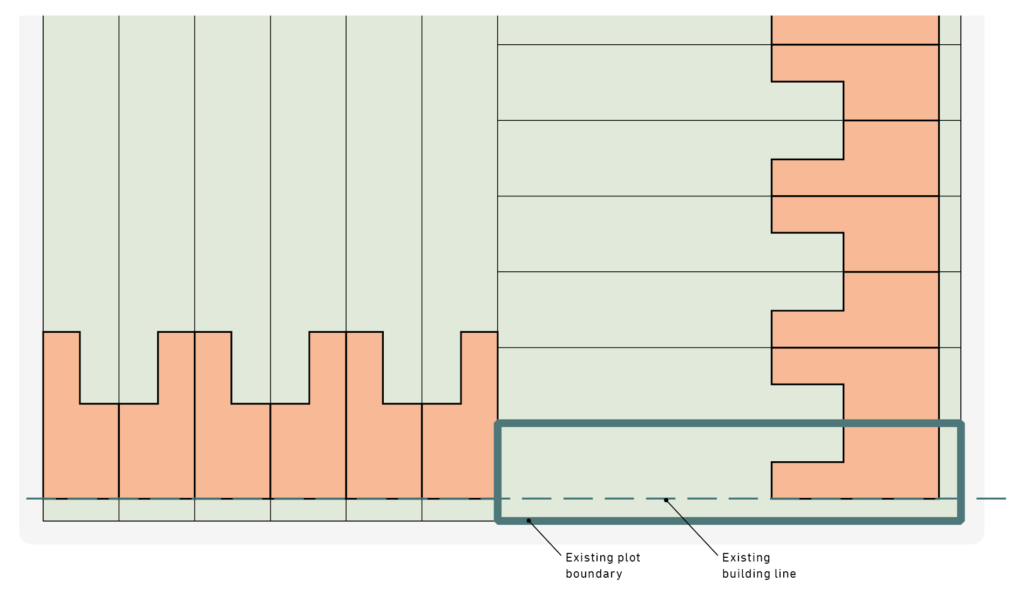

Depending upon the distances between proposed and existing properties, the prevailing building line can vary from the primary to the secondary street.

Where a 10m or more gap exists between the new dwelling and its nearest neighbour, the building line of the host property can be adopted if this is closer to the public highway (figure 130).

Where a gap of less than 10m exists between a new dwelling and its immediate neighbour, the new dwelling should adopt the building line of this property (figure 131).

Proposed dwellings without a frontage to the public highway fall under the category of backland development. See section 31 for guidance on this type of development.

27.4. Collective development

Where neighbours collaborate on development, a greater number of homes can often be delivered compared to when householders act alone.

A minimum acceptable distance between the principal windows of habitable rooms in the rear of the existing dwellings and blank walls must be achieved. Generally this distance should be no less than 10m.

Care must be taken to avoid significant overlooking of neighbouring gardens. Steps should be taken to avoid direct overlooking of rear gardens and planning applications should demonstrate how existing residents’ privacy is not unacceptably compromised by new development. Overlooking of the first 10m of a neighbouring garden will not usually be acceptable. More flexibility can be applied where some overlooking of gardens longer than 10m occurs, and in this case the avoidance of overlooking should not prohibit the construction of new homes where all other planning policy ambitions are achieved.

An analysis of the impact new development has on adjacent homes should be provided as part of a planning application, demonstrating that adequate levels of natural daylight are maintained to the principal windows of habitable rooms, and that existing gardens are not unacceptably overshadowed.

Demonstrating compliance with the principles of the BRE “Site Planning for Daylight and Sunlight” publication is usually sufficient for infill development. Where these requirements cannot be met, more detailed computational analysis may be required.

All new dwellings will need to be compliant with current space standards, as outlined in the Nationally Described Space Standards and the London Plan. Note that minimum room widths set out in these documents will need to be achieved.