32. Garages and Yards

32.1. General principles

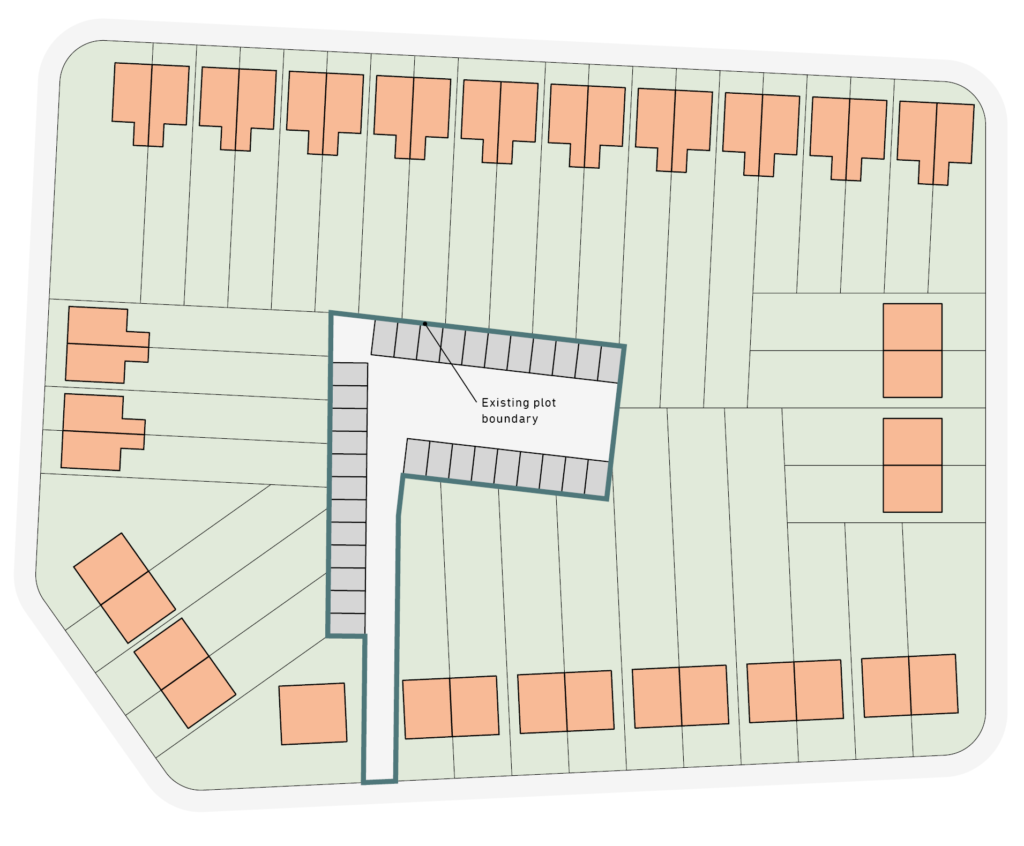

Disused garages and yards often occupy space between the end of long gardens within urban blocks, and are usually reached via a narrow access from the public highway.

In many cases such garages have fallen into disrepair as they are no longer large enough to accommodate modern cars, and can be a source of anti-social behaviour.

Planning applications which propose the replacement of existing garages or workshops will need to demonstrate these structures are no longer required. A parking survey may also be required.

Where backland sites are occupied by non-residential uses, the change of use to residential will be resisted unless sufficient allowance is made within the scheme for these uses to continue. Where the development itself will involve the temporary disruption of non-residential activities, assurance may be sought that temporary relocation of any businesses occupying the site is secured, and that provision for their return once work is completed has been made.

The development of new homes on such sites can bring benefits to adjoining residents, including increased security.

Where a site has more than one access point from the public highway it is defined as a mews rather than a garage or yard site. See the appropriate section of this document for specific guidance on mews sites.

Where development is proposed within Conservation Areas, the accompanying character appraisal takes precedence and applications should demonstrate how proposals are in accordance with it.

New residential development on sites previously occupied by garages and yards should make adequate provision for safe access for pedestrians, including artificial lighting, even road surfaces, passive surveillance and, where necessary, sufficient width for vehicles and pedestrians to pass one another without pedestrians having to step to one side.

In areas of Lewisham which benefit from a high level of accessibility to the public transport network, car-free developments will be supported; conversely, developments which propose car parking will not generally be supported, with the exception of spaces dedicated to wheelchair parking.

Where new dwellings are located some distance from the public highway it may be necessary to make an allowance for certain vehicles to enter the site, eg. for deliveries and emergency vehicles. In these cases a turning head should be provided, although steps should be taken to ensure that this is not used as a parking space for residents’ own vehicles.

Under no circumstances will gates across the entrance to access routes into backland development be supported. Rising bollards or similar devices which prevent vehicle ingress, but do not inhibit pedestrian access, are acceptable, providing that there exists a strategy for allowing emergency and other service vehicles into the site where necessary.

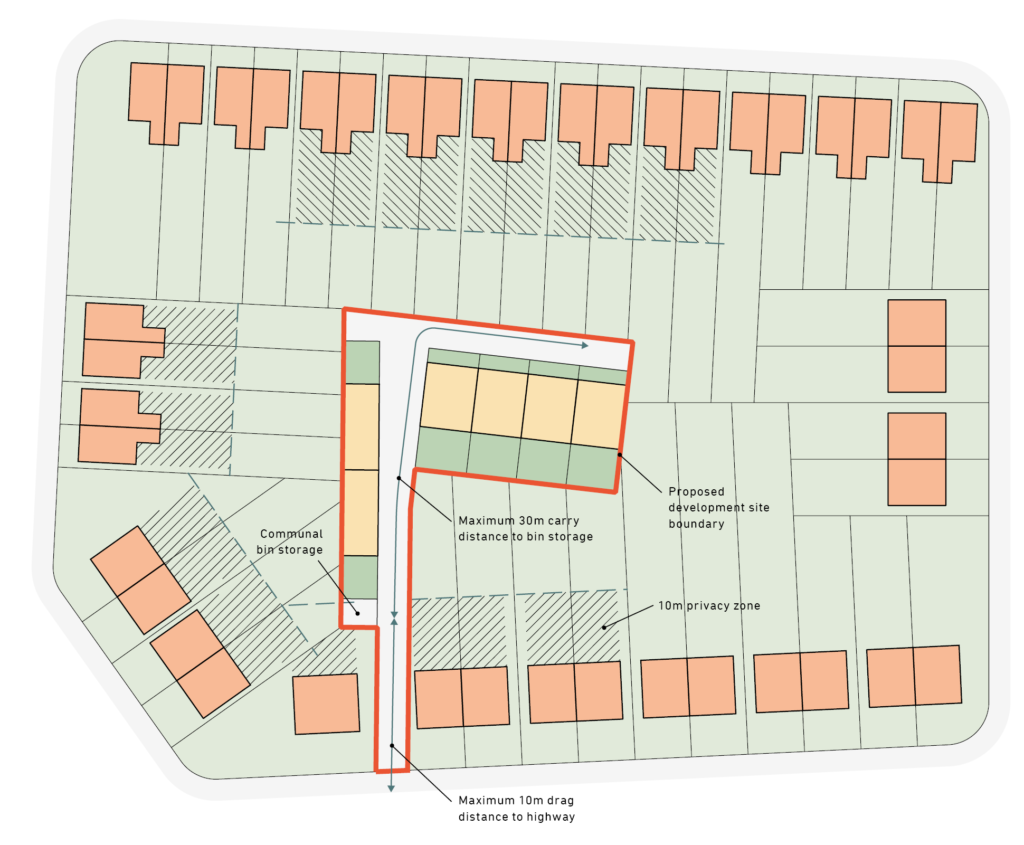

Access for waste and recycling collection must be considered from the outset in any design. In general terms, operatives are able to drag waste and recycling bins up to 10m from outside the front door of dwellinghouses, or a dedicated collection point, to the highway.

Where dwellings are proposed with front doors more than 10m from the public highway, a dedicated waste and recycling point should be designed into the development. Residents should have to carry their waste no more than 30m from their front doors to this collection point. In most cases this places an effective limit of 40m between the public highway and the front door serving a new dwelling.

In limited circumstances it may be possible for waste collection vehicles to reverse up to 20m into an access way serving a backland development, however, this depends on the geometry and safety of the junction with the public highway and an adequate width to allow both waste collection vehicles and pedestrians to pass safely. Furthermore, given the complexity of this manoeuvre waste collection vehicles cannot be expected to reverse into backland sites serving fewer than 10 dwellings.

Where insufficient provision is made for the storage of waste, this can result in unhygienic conditions and contribute to a cluttered and untidy public realm.

In all cases early engagement with Lewisham’s waste and recycling team is encouraged to ensure that sufficient provision is made within the layout of the site for this purpose.

In any planning application for backland development where access to new dwellings is reliant on a single route from the public highway, the applicant will need to demonstrate that a high-quality, safe and even surface can be secured. The use of planning conditions to ensure that necessary improvements are implemented prior to occupation of new homes may be applied to any planning approvals. Applicants are encouraged to check, and secure where necessary, the right of way or ownership over any area of the site which falls outside the application boundary.

Due to their proximity and relationship to existing homes, backland development sites must take care to respect the privacy enjoyed by neighbouring properties. New development should avoid, where possible, direct overlooking of adjoining rear gardens, and applications that propose new dwellings where the windows of habitable rooms look directly over the first 10m of existing rear gardens will not be supported.

Within new development itself, privacy and overlooking distances can in some cases be relaxed to ensure the optimum use of a site, although applicants will need to demonstrate how the spirit of the policy is being achieved in other ways.

New development should make efficient use of available space. In most cases terraced or semi-detached dwellings are preferable to detached properties.

The height of new development should generally follow that of the predominant height of the properties surrounding it. In this case, the number of floors is considered to include substantial pitched roofs.

Where development is proposed within Conservation Areas, the accompanying character appraisal takes precedence and applications should demonstrate how proposals are in accordance with it.

32.2. Backland sites and existing employment uses

Many backland sites in Lewisham are occupied by existing commercial uses such as workshops. These premises provide vital accommodation for small businesses, and planning applications for new homes which involve the net loss of employment space will not be supported.

However, where the intensification of an existing site can be achieved without the net loss of employment space, development will usually be supported, provided that all other planning policy requirements are met.

Depending on the nature of the existing employment use, some consolidation may be acceptable, for instance, where single-storey buildings could be replaced by two-storey accommodation without compromising the operational requirements of the incumbent business.

In exceptional circumstances, and where it can be demonstrated that there is no longer a demand for a particular type of employment space, a reduction in floor space may be accepted where the new accommodation is of a superior quality than the premises being replaced. In this case, evidence should be provided that a change in planning use class (for example, from E(g)(i) to E(g)(ii)) will result in not net loss of jobs, and will result in a use which is more in demand in the local area.

The process of redevelopment itself can be disruptive to existing businesses, and where appropriate a guarantee may be sought through legal means to temporarily re-house an existing tenant so that their ongoing business operations are not put in jeopardy by the works.

These sites are often reached by narrow accessways from the public highway. In this case the principles set out on the preceding pages should apply.

There should be a clear separation between the residential areas and the commercial uses. Vehicles serving the commercial buildings should not have to pass through a residential zone. Likewise, access to new homes should not be through the non-residential zone. Shared accessways from the public highway will be accepted. In these circumstances special care should be taken in the design of shared surfaces to ensure that they are safe for pedestrians.