28. Corner Development

28.1. General principles

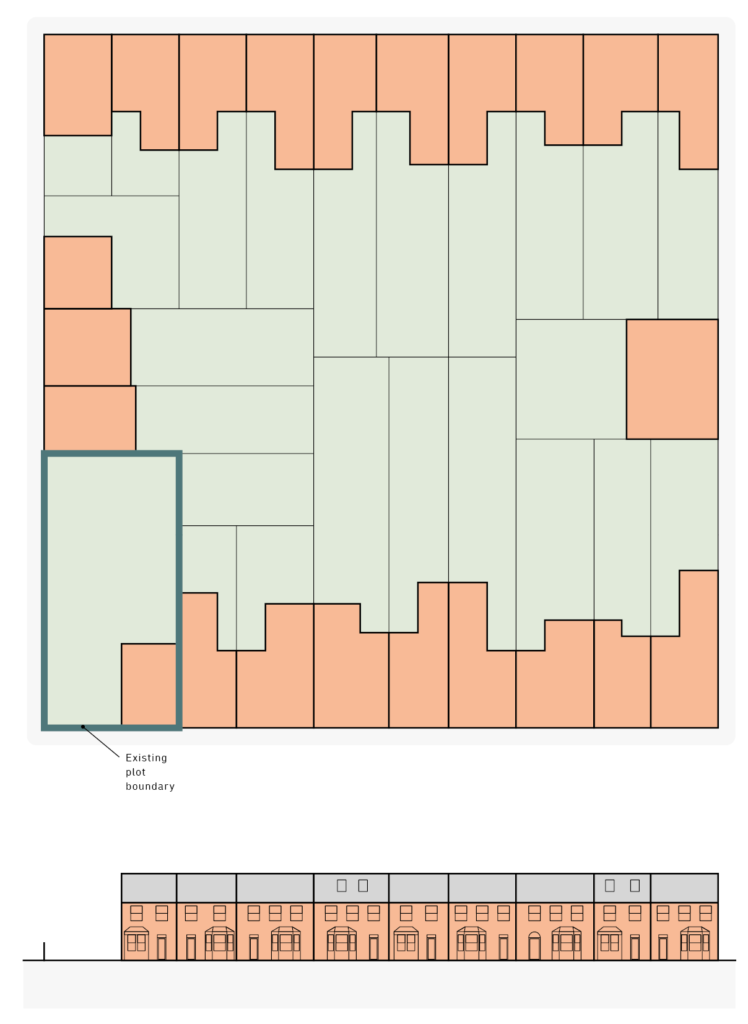

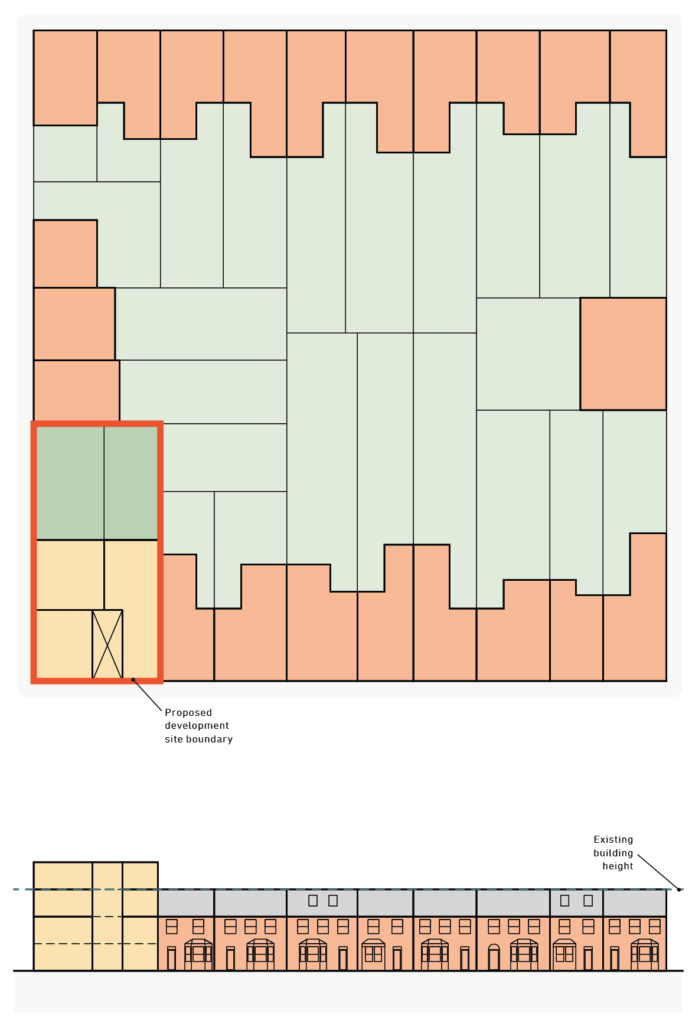

Corner development occurs on the junction of two streets, either through the demolition of an existing building where this makes poor use of available space, or where it results from piecemeal development that has occurred over a long period of time.

Generally, corner sites are considered to be those where two streets meet one another at an angle less than 135 degrees.

New development on the corners of streets can help establish, or reinforce, local identity and assist with orientation and wayfinding.

Any new development on street corners must achieve a high degree of design quality. These are typically locations suitable for distinctive buildings which are marginally taller than their neighbours.

It is important that active frontages are provided to both primary and secondary frontages, with front doors and windows to the street.

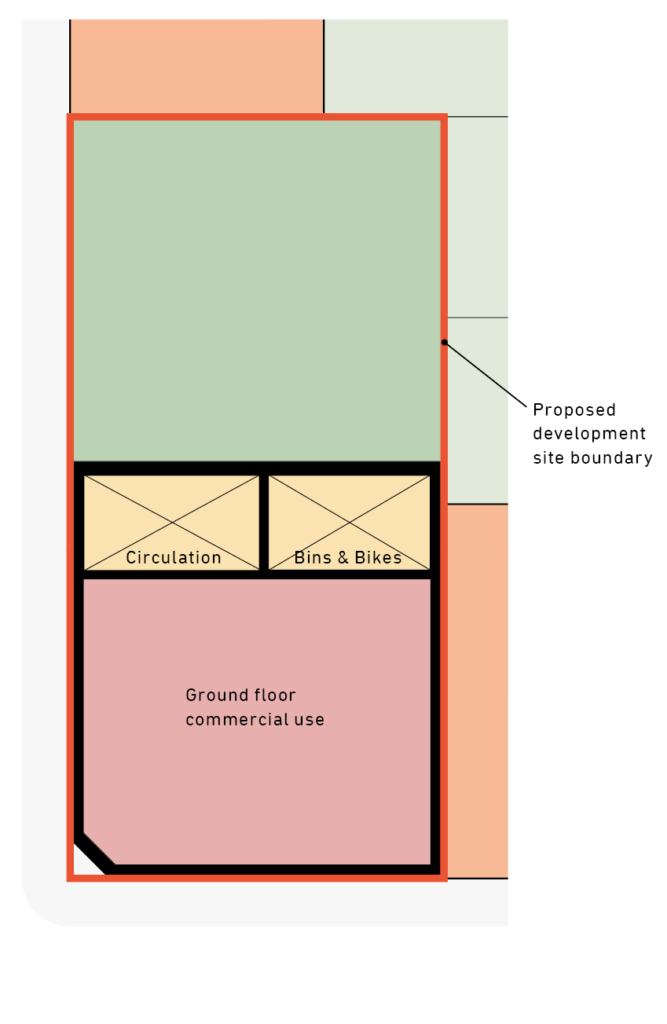

On larger sites the ground floor of corner buildings can be occupied by non-residential uses such as retail. Applications which propose such uses will generally be encouraged, provided that all other planning policy objectives are met.

28.2. New development on corner sites

Generally, corner plots present an opportunity for slightly taller buildings than might be possible within the middle of a street. A building of architectural character and high degree of design quality can help establish a sense of place, contribute to a neighbourhood’s sense of identity and assist with orientation within a wider setting.

Where new development which is taller than its neighbours is proposed, planning applications should demonstrate a high degree of architectural quality.

Where corner sites are already occupied by existing homes, a creative reuse, retention and extension is more sustainable, and therefore preferable compared with demolition and rebuilding. Creative ways of achieving this will be recognised in planning decisions.

Planning applications which propose a net loss of family housing will not be supported, and any existing family homes which are lost due to demolition will need to be replaced within any proposals for new development.

Corner sites tend to benefit from a significant frontage to the street, and less to rear gardens.

External amenity space should be inset from street-facing elevations and should not overhang public footpaths or the public highway.

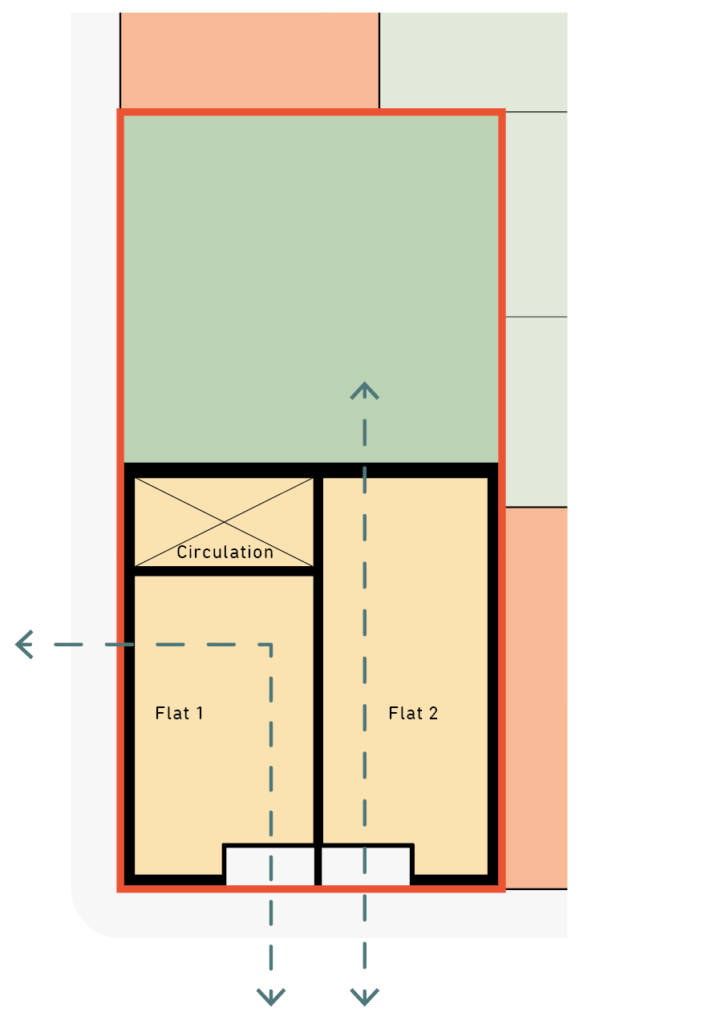

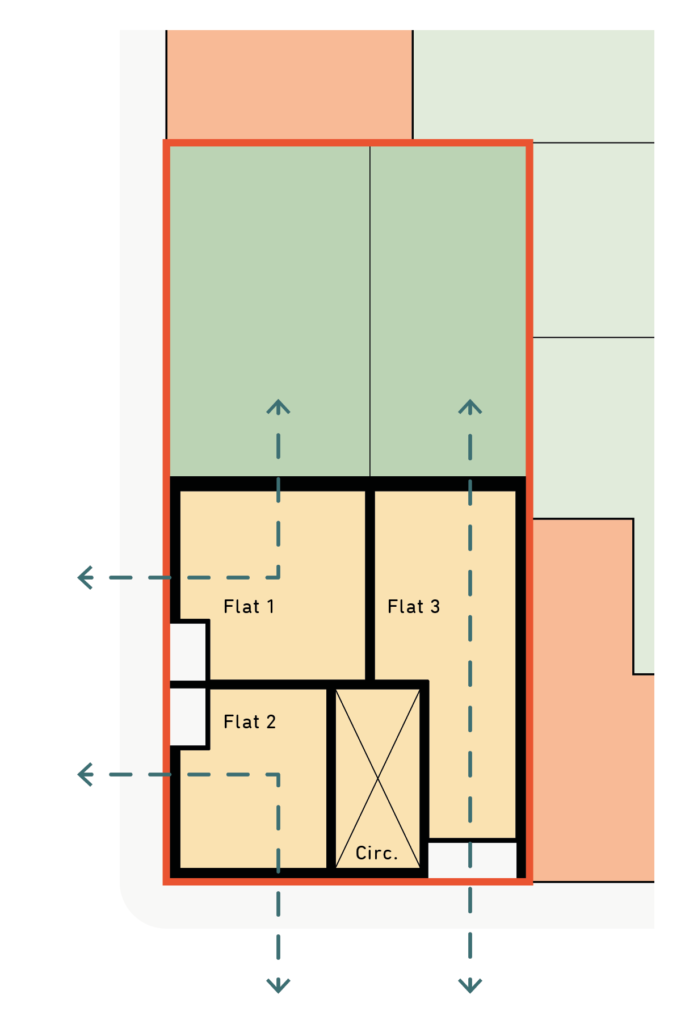

Active frontages to the street are encouraged, but this should not be at the expense of providing future residents with acceptable privacy. Ground floor, street-facing balconies are discouraged, as are new single-storey dwellings with only a street-facing frontage.

Where the layout of new corner development results in ground floor accommodation with frontages facing only directly onto the street, non-residential uses in this location are encouraged: either shared cycle storage for the development, or alternative planning uses, are encouraged.

All planning applications for corner infill development should demonstrate how their design positively responds to an understanding of local character and its immediate context.

Corner development can be combined with other forms of infill development, such as side street infill, providing that all requisite planning policies are complied with.

28.3. Mixed-use developments

Because of their prominence within the streetscape, corner development presents an opportunity to introduce or enhance non-residential uses.

Because street-facing residential accommodation should generally be avoided on corner plots, an active frontage can be provided through small-format retail (planning use class A1), restaurants and cafés (planning use class A3) and so on.

Where commercial uses are proposed for the ground floor of mixed-use developments it is likely that a taller floor-to-ceiling height will be required. This can help accentuate the prominence of the building and differentiate between the different uses within the building.

On sites with limited pavement width, careful consideration should be given to the footprint of the ground floor. A mitred or rounded corner can help pedestrians navigate their way around tight corners.

A clear distinction should be made in the exterior design of new development between residential entrances and those of non-residential uses.

Provision must be made for the secure storage of bicycles and waste at ground floor level. This should be fully integrated into the proposed layouts, and applications which do not allow sufficient space for these items will be opposed.

On small developments providing a mix of commercial space at ground floor and new residential accommodation above, level access to upper floor homes is not mandatory but is encouraged where this can be achieved economically and without compromising other aspects of the design.

Where mixed-use development includes ground floor uses which involve food preparation, or other commercial uses, careful consideration should be given to the coordination of extract equipment and other associated plant with the residential uses above. Extract ducts must be located well away from opening windows and vertical ductwork must be integrated successfully within the overall design of the building and not tacked-on as an afterthought.