7. Conservation Areas

7.1. What are Conservation Areas?

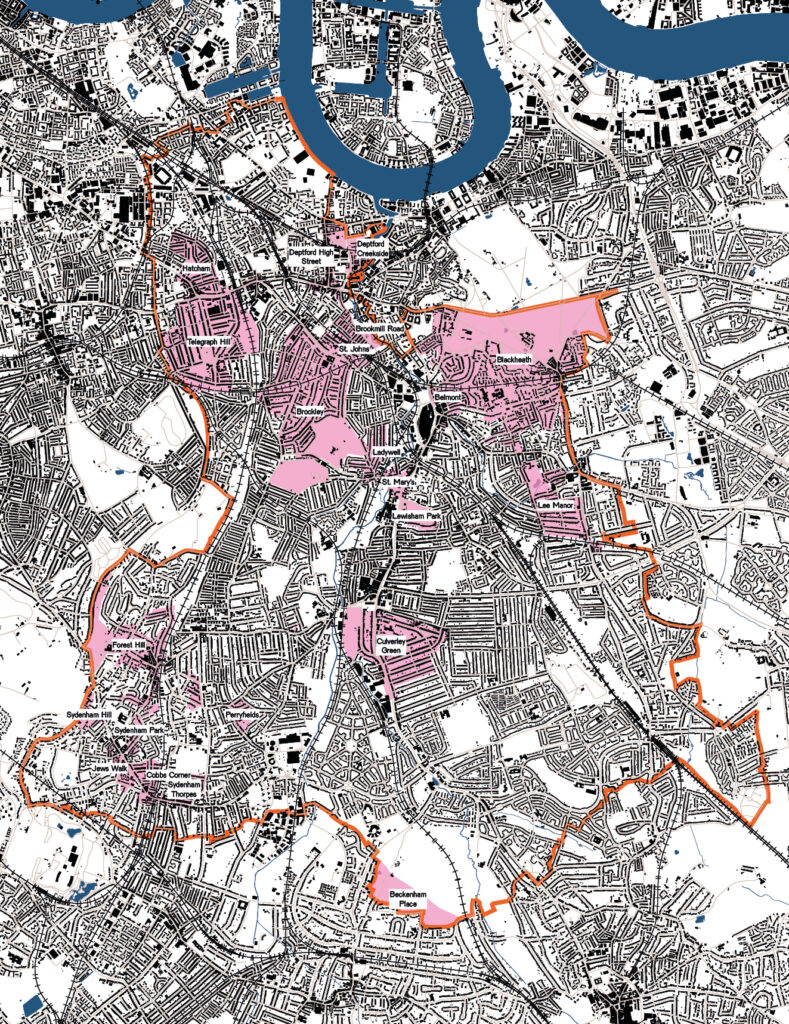

Conservation Areas are areas that have historic or architectural interest, and where planning policy seeks to preserve or enhance this character.

Many of these have appraisals and / or Supplementary Planning Documents (SPDs) that describe the significance of these areas. In order to protect the character of Conservation Areas, development will generally be subject to more stringent planning controls to ensure that new development responds sensitively to the particular characteristics of that Conservation Area, which may relate to height, roofline, materials and building use. All trees in Conservation Areas are protected.

7.2. A rich history

All development sites, wherever they are in Lewisham, will have a history and surrounding built context. Within Conservation Areas, where Conservation Area appraisals have been adopted, this character is accessibly described and celebrated, but existing architecture across the borough can also inspire and inform the character of new development.

Many sites will have been built on before, sometimes more than once. Previous buildings will have been demolished for all sorts of reasons, both good and bad, from pioneering projects to improve health and wellbeing, to the trauma of wartime bombing. Finding out about these demolished buildings will help explain the shape of plots and road layouts, the names of streets and localities.

Every site will have diverse neighbours and structures built for many different reasons with different levels of skill and care. Yet all contribute to the history of an area, and are experienced – for good or bad – by hundreds, if not thousands of people on a regular, occasional or one-off basis.

Both the disappeared past and the still present tell stories, and what’s added today has the opportunity to enrich this narrative and should seek to do so in a positive way. Lewisham already has a forward-looking attitude to conservation, in its Conservation Area appraisal documents the borough variously recognises the “creative spirit” of the murals and graffiti at Deptford Creek, and cites Blackheath Conservation Area as one where modern buildings stand equal to those of earlier centuries. The brutalist concrete Lewisham College building is identified as having a positive impact, and Lewisham Park Towers, a group of high rise blocks from 1965, is recognised for its architectural interest and is noted to have aged particularly well.

This should reassure potential developers that – although the majority of the borough’s Conservation Areas recognise the genial character of commercial suburban expansion – there is great diversity in Lewisham’s past and a willingness on the part of the borough to embrace innovation, both within its Conservation Areas and beyond.

7.3. Past and present

To what extent should the architecture of small sites make reference to the buildings around them? Such sites, be they infill, corner, vertical intensification or backland, will be in contact or close proximity to their neighbours. Should new buildings strive to be contemporary, with little reference to the past? Can they reference the past in a meaningful way without becoming trite or superficial and lapsing into pastiche? How does one make good new contemporary architecture in a rapidly evolving and vibrant multicultural city?

Architecture struggled with its history throughout the twentieth century, but is now experiencing a new freedom to explore tradition, pattern and decoration with a mindful playfulness which has the potential to draw on previous examples creatively where appropriate. The skills are out there both to knit together areas which are clearly fractured or damaged, and to insert new structures comfortably into established neighbourhoods.

Neither music nor fashion would view innovation or referencing the past as an either / or situation. We are totally comfortable with the concept of sampling, or being inspired by the mood of a film or iconic photoshoot. Quoting patterns, shapes, proportions and rhythms is an acknowledgement that the past is a rich source of cultural expression, to be celebrated, critiqued and reinvigorated as part of a lively on-going dialogue. It is second nature to artists in many fields.

Social media can encourage us all to cut and paste, to edit and embellish, for fun, for political or social comment, to create, to enjoy and share. We don’t worry that we will feel ignorant if we don’t pick up on every single allusion, and we don’t see the originality of the final product as being diminished by drawing on what has come before.

When it comes to architecture, inhibitions set in. To reference the past can be seen as having nothing new to say; to lack imagination. Architecture is just beginning to shake off some of these restraints and become more comfortable with its past. This is great news that’s really relevant to how we address infill sites. There will be no one correct solution for any of the sites across the borough.

7.4. Intangible heritage

Local distinctiveness can be intangible as well as physical. A great example in Lewisham is the work of Edwardian developer Ted Christmas, whose eye for design and quality of imaginative detail is rightly cherished. He named his houses and ensured the longevity of these names by incorporating them in highly decorative stained glass front doors. What is not immediately obvious is that the initial letters of each name along the street spell out “Ted Christmas”. To live here and know this, is to be in on a secret story hidden in plain view. Are there opportunities to incorporate similar devices today? Could more be made of the memories of Lewisham’s past residents to enrich the sense of local identity?

Famous past inhabitants of Brockley Conservation Areas included actress Lilly Langtry and music hall entertainer Marie Lloyd. The Tetley responsible for the world’s first teabag lies in a Lewisham church yard. There is scope for new infill projects to reference these stories and undoubtedly many more, including stories from the more recent past, which could help today’s residents stop to ask “what was it like here back then?”, and fire an imaginative engagement and sense of belonging.

7.5. Modern lifestyles

What we need from our homes has changed. Modern lifestyles have meant that the way that our buildings look is often different.

Some things remain constant:

- We want our homes to feel safe and secure

- We want them to give us privacy and seclusion when we want it, but we also want to get to know our neighbours and feel part of a community

- We want to be warm, dry and free from condensation

- We want our homes to be easy to keep clean and smart

All sorts of aspects of day-to-day life have changed radically from when some of our homes were built:

- Electric car charging points, bicycles, electric bikes, scooters and electric scooters, prams and buggies (now more compact and manoeuvrable)

- More parcels, secure drop-off when we are not at home, chilled drop-off for supermarket orders, fewer and fewer letters

- We want the ability to work from our homes, a greater connection with our gardens and open-plan living