9. Development Flowchart

9.1. Introduction

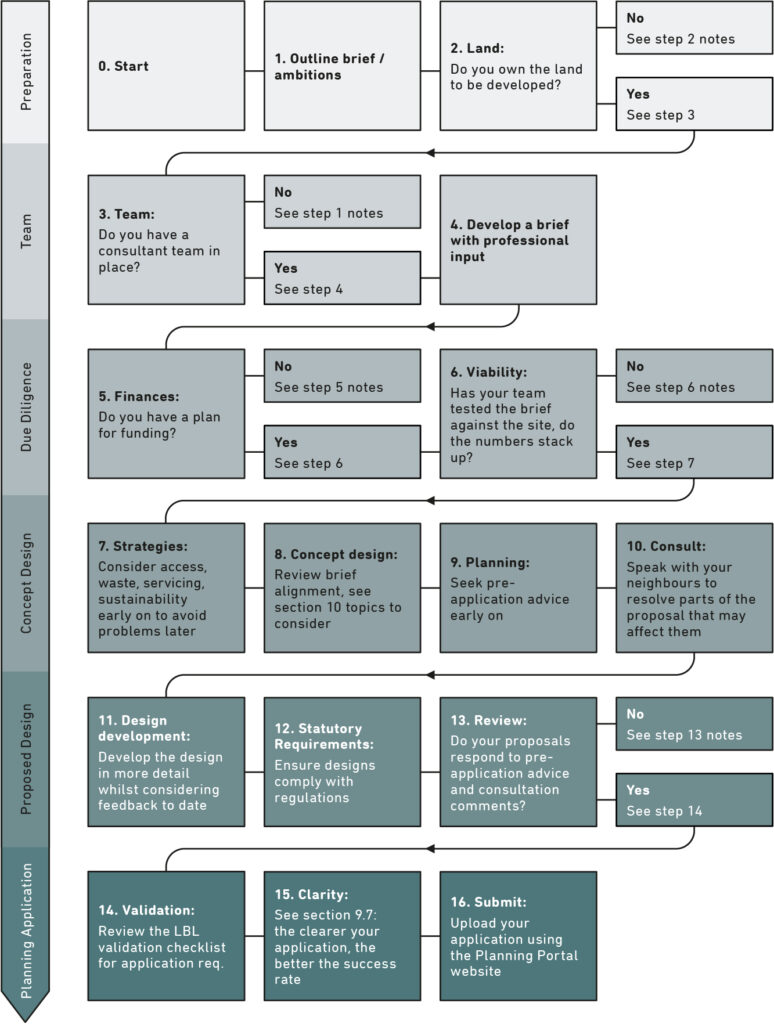

The process of obtaining planning permission for a small sites development can seem both vague and overwhelming to new developers and residents. This section aims to break this down into a series of steps to help those working on small sites to understand the process and follow a working pattern that reduces the risks involved, whilst increasing the quality of the outcome. More experienced developers may have their own processes, but this guidance should still provide a helpful comparison as to the expectations of Lewisham Council. The flowchart to the right (figure 12) provides an outline of the process, whilst the following text breaks down these steps in more detail.

9.2. Preparation

Step 1 – Outline brief

Small site housing developments come in many forms, from a one-off private houses, to a community of self-builders working together to collectively achieve their housing needs. Going into a project it is important that you begin with a clear idea of the type of project you want to achieve. This way you will better be able to find the proper guidance, advice and consultants. Your initial brief is likely to adapt, evolve and become more specific as the project progresses.

If you are not sure where to start with this, lots of built environment professionals offer a service where they can help you to understand what is likely to be possible and therefore help you to define a brief. It is a good idea to consult an architect for this to help you understand the feasibility of your project, the capacity of the site or recommend other suitable professionals if appropriate.

Step 2 – Finding land / identifying a site

Finding land to develop is often one of the key barriers to developing new homes. Small sites offer an opportunity to increase the diversity in housing development by encouraging development of previously unconsidered land.

Some people entering into a small site development will already own their site. If you own any land in Lewisham (even if it already has buildings on it), it may be worth considering if development is an option. Even when demolition of existing dwellings is involved, projects can often be more viable, increasing the overall number of homes. If you do already own the land you will need to consider whether you want to develop the land yourself, or include another developer in you plans.

In addition to developing a site which you own, it may be that your proposal could be of more value if delivered jointly with a neighbouring plot. See section 18 for more information on this.

If you don’t already have land there are several options to consider. You may have seen a plot in the local area which you feel would be suitable and would consider purchasing to develop yourself – you can see in the site types section what a typical small site might look like. Land Registry provides a cost-effective service which you can use to identify the current owner of a site. You can obtain both the Title Register (which includes ownership information) and Title Plan (which shows the extent of the site) for no more than a few pounds each (beware of third-party sites which offer a similar service as they can be much more expensive).

Lewisham keeps a number of registers which might help, including a list of brownfield land (see glossary) and the Mayor of London, and Community-led Housing London Hub websites offer guidance on alternative housing models including:

- Self-build

- Community Land Trusts

- Co-housing

- Co-operative housing

- Affordable housing

Lewisham Council maintains a register of people who are interested in finding out more about self-build or custom-build houses in the borough. This can be found at:

https://lewisham.gov.uk/myservices/planning/policy/self-build-and-custom-build-homes/

9.3. Team

Step 3 – Consultants

To develop a small site for housing, and to ensure a quality outcome, you will likely need to engage a range of professional services. Each site is different – its heritage context, biodiversity, flood risk, and so on – and as such the information required for every planning application will differ.

Engaging an architect and / or planning consultant will help you to develop a proposal that meets your ambitions whilst also being compliant with the relevant statutory policy and guidance. An architect will also help to identify the types of professional services a project requires and guide you through the development process.

It is advisable to employ a registered architect. Refer to the Architects Registration Board (ARB) or the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) for guidance on selecting a registered architect. Working with reputable professionals with good experience is more likely to achieve a high quality design, increase site efficiency, and reduce planning risk, ultimately increasing the value of a development. Note that appointing a consultant on the basis of a low fee doesn’t necessarily save money on a development in the long run. It is recommended that you obtain references from potential consultants and make sure they are a good fit for you.

An architect should be able to design your proposal in order to respond to any identified constraints and may be able to develop your initial ideas to provide a more creative proposal than you originally envisaged, saving you time, optimising your budget and adding value to your property. They will also help to guide you through relevant, up-to-date legislation and regulations.

Depending on what financial risk you deem acceptable, it is likely that additional consultants will be needed, such as a structural engineer, services engineer (water, heating, and electrics), and quantity surveyor (cost). It is usually better to spend money on professional fees and to fully understand the estimated cost of your development prior to progressing to a planning submission in order to reduce the risk of getting permission for something you cannot afford to build.

Similarly, appointing a heritage consultant is particularly helpful if your site includes a listed building, is in a Conservation Area, or next to listed buildings. A heritage consultant can provide the historical context which will inform the design and demonstrate to the planners how your proposal preserves or enhances what already exists.

Details of accredited heritage consultants can be found on the Institute for Historic Building Conservation’s Historic Environment Service Provider Recognition website.

Use Lewisham’s planning website to review previously-approved planning applications, where you can find which consultants were involved, and to obtain their contact details.

Step 4 – Briefing

Regardless of the size of the project, a clear, written brief is an invaluable tool and this should be developed from the outset in collaboration with the professional team you have employed. It should set out your required outcomes (floor area, sustainability credentials, sales value), and key constraints (planning, programme, funding, site access). A project brief will generally be updated and develop as the design of a project progresses.

9.4. Due diligence

Step 5 – Finances

Outside of the more traditional methods of securing funding (eg. business loan, re-mortgage), there are ever-increasing alternatives. The Mayor of London’s website gives extensive guidance on the resources available to those looking to develop small sites. These exist as both grants and loans and access to them varies depending on the type of development you are intending to bring forward.

Step 6 – Viability

To help reduce the financial risk to a project, feasibility studies can be undertaken at a relatively low cost which will help to identify if your brief is achievable on the site, together with an estimated project cost. This will be an invaluable tool to develop a financial appraisal of a development, how estimated costs align with your budget, and whether completion and sales be achieved within your required timeframe for funding.

Viability studies go beyond simply understanding a budget, and take into account the potential income a project can provide, as well as the various commitments and fees involved to understand if the project is financially feasible. Small sites play a key role in providing the housing Lewisham needs, and therefore have an important role in providing affordable homes. Viability studies help developers to understand the best approach to delivering on site affordable homes.

An important cost to consider is the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) cost. New homes will be required to contribute a CIL payment which allows the council to deliver the infrastructure needed to support them. Some developments may be eligible for relief or exemption from Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL), including residential annexes and extensions, houses and flats which are built by ‘self-builders’, social housing and charitable development. For further details please see the government guidance at www.gov.uk.

Feasibility studies vary depending on the stage and nature of a project, but would typically be carried out by an architect, who could then work with a quantity surveyor to test proposals for viability.

9.5. Concept design

Step 7 – Strategies

There are a number of key strategies that small sites projects need to consider to ensure that they can function. These will vary from site to site as constraints will vary, but these might include optimisation, access and sustainability.

In order to meet housing demand, the London Plan requires planning authorities to assess the efficiency and capacity of proposals, and to resist those which are deemed an under-development of a site.

Local and regional policy seeks to guide developments to make the most efficient use of land. As outlined in section 9.3, a skilled designer can help to maximise the efficiency of a site, be that increasing the number of dwellings or creating a larger garden space than you thought possible. Similarly, your proposal may be more successful if delivered jointly with neighbouring landowners. See section 18.3 for design guidance on working together with neighbours.

A key constraint on small site development is the need to ensure that the new homes can be properly serviced and provide safe access for the occupants as well as organisations such as waste collection and the emergency services. This can be particularly challenging when working on sites where the new homes do not have a street frontage.

We are in a climate emergency and urgently need to reduce carbon emissions. In the UK, 49% of annual carbon emissions are attributable to buildings. All planning applications in Lewisham are required to include a Sustainable Design Statement as part of the submission, setting out how sustainability design principles have been integrated into the proposal. Understanding the strategy for achieving a sustainable, low-energy building early on in the design process helps to achieve these targets in a more cost-effective and efficient way. Refer to sections 11 and 21 for more information, and consider the advice of the green design toolkit in section 14.

Step 8 – Concept design

The concept design stage is important in understanding how the scheme might respond to key contextual prompts and how it addresses the brief. As this stage it is useful to factor in an opportunity to review the emerging scheme to de-risk it ahead of moving forward with detailed design. Some key topics that should be covered at this stage are set out in section 10 as part of the advice on writing a design and access statement, which is a necessary part of any planning application. Considering these topics early on will make the preparation of a design and access statement more straightforward.

Step 9 – Pre application advice

Lewisham offers a pre-application advice service. This allows you to discuss your development proposals with a planning officer and receive advice on your potential planning application before you submit it or whilst working through your design to test some of the potentially contentious issues with officers. Applications are more likely to be approved quickly following a positive pre-application stage, however, this does not guarantee the outcome of your application.

Discussing your proposal early on with planning officers can reduce planning risk and helps to identify:

- If the principle of development is acceptable

- If any changes to the design are necessary

- What information is needed before you finalise and submit your proposal

Step 10 – Consult your neighbours

It is generally beneficial to consult local residents and anyone else who may be affected by your proposal regardless of the size and location of your proposals.

Talking to people is an opportunity to let them know how you’ve arrived at your proposal, and to discuss any concerns or interests they may have. A consultation process can highlight issues the scheme might create which you may not have considered, and where relevant, allows the design to develop in response to this.

Anybody may also write into the Council to offer support for your scheme or to object to it. Support for the application does not mean it will be approved, nor do objections mean that your application will necessarily fail, but all comments will be taken into account in the planning decision.

Consultation should be recorded as part of a planning submission to demonstrate to the planning department how the proposal has evolved and taken into account local feeling and site-specific issues.

9.6. Proposed design

Step 11 – Design development

Design is an iterative process, and there will likely be several versions of a proposal before a final design is reached. For example, as noted in step 9, a design will usually develop following pre-application discussions in order to align more closely with planning officers’ requirements, discussion with neighbours and other community groups. The design should develop from your brief, whilst also considering statutory requirements within planning policy and building regulations. See section 10 for more information on what sort of design development information Lewisham expects to see in a Design and Access Statement.

Step 12 – Statutory requirements

All small sites building projects need to comply with the Building Act to ensure that they are safe and of a sufficient standard. The easiest way to do this is usually to follow the requirements set out in the Building Regulations. These regulations include stipulations on spatial parameters as well as elements that might impact the cost and viability of the project and therefore should be considered prior to applying for planning permission.

Understanding the requirements of planning regulations is also important for your scheme to ensure that you are applying for a scheme that can be granted permission by the council. This includes meeting Nationally Described Space Standards (NDSS) as well as the accessibility requirements set out in the London Plan.

Step 13 – Design review

As at step 8, it is important to review your scheme regularly in order to de-risk the process and make sure that the proposal reflects your brief and is likely to receive planning permission. Has the design responded to the pre-application advice, consultation with neighbours and any community groups? Does the design meet your brief and is it financially viable?

9.7. Planning application

Step 14 – Validation

All planning applications have a minimum requirement for the information required to determine them. If you do not provide this information then your application cannot be validated and the application process cannot begin. Lewisham Council’s website sets out clearly what these are.

To understand what you need to submit you will need to know what planning designations your site sits within. For example, there are different requirements when working in a Conservation Area or in protected open space. It is important to know these early in the design process as they can have a significant impact on the way the site is designed. Lewisham has an interactive map where you can find out the designation on your site.

Depending on the designation, as well as the type and extent of your proposals, various documents may be required such as a heritage statement or a sustainability monitoring form. For all small sites applications a Design and Access Statement is required. Advice on this is given in section 10.

Step 15 – Clarity

Before submitting your application, take time to ensure that the information contained is clear and concise and properly communicates your proposals.

Once your planning application is ready, it should be submitted digitally through the national planning portal. Once this is done, it will be sent automatically to Lewisham’s planning officers to check validation and determine.